Poverty in Canada: Most say governments are doing too little, but disagree on what should be done

Most Canadians say people are poor because of circumstances outside their control, not a lack of effort

Aug 1, 2018 – Canadians overwhelmingly see poverty in their communities as increasing, rather than decreasing, and they believe their federal and provincial governments aren’t doing enough to reverse this trend. Just what should be done, however, is the subject of considerable disagreement.

Part Two of the Angus Reid Institute’s in-depth study of poverty in Canada finds Canadians largely agree wealth and poverty are more the result of circumstance than of personal character, that rising income inequality is unacceptable, and that a national infrastructure program would be a good idea for addressing these issues.

The population is considerably more divided on questions of government benefits for the poor, with wealthier individuals and political conservatives generally opposed to increasing spending on these programs and preferring to place greater emphasis on hard work.

These findings also play out across the four segments of the spectrum of lived experience identified in Chapter 1 of this report: The Struggling, the On the Edge, the Recently Comfortable, and the Always Comfortable. The four groups hold strikingly similar attitudes on many aspects of poverty in Canada, but there is significant disagreement between the two Comfortable segments and the two Struggling ones over the role of government in addressing poverty today.

More Key Findings:

- Two-thirds of Canadians (65%) say the federal government is doing too little to address poverty, and approximately the same number (64%) feel this way about their provincial government

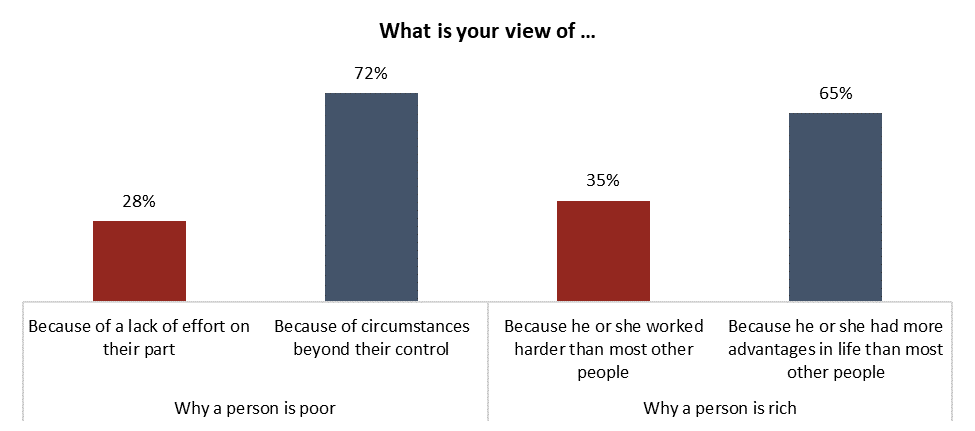

- More than seven-in-ten (72%) say poor people are poor because of circumstances beyond their control, rather than a lack of effort on their part

- A similar number (65%) say wealthy people are wealthy because they had more advantages in life, rather than because they worked harder than other people

- More than eight-in-ten Canadians (82%) say “the growing gap between the rich and everyone else is unacceptable,” and nearly three-quarters (74%) say it’s getting harder to maintain a middle-class standard of living where they live

INDEX:

- How Canadians perceive poverty and the poor

- Attitudes across the lived experience segments

- Unacceptable or a fact of life?

- Are governments doing enough?

- Strong support for expanded governmental intervention

- Notes on methodology

Introduction

This special Angus Reid Institute study on poverty in Canada today sought to capture personal experiences with – and attitudes toward – this topic. The first chapter of the report was released on July 17, 2018 and dealt with defining and quantifying poverty through the day-to-day economic struggles of Canadians.

This second chapter of the report on the findings of this study will focus on attitudes toward poverty in Canada, including the perceived prevalence of poverty in Canadian communities, Canadians’ feelings of empathy for the poor, views of governmental handling of this file, and support for various proposals for alleviating poverty.

How Canadians perceive poverty and the poor

How do those living in poverty end up there? Is their situation a product primarily of their own choices or of circumstances beyond their control?

For more than seven-in-ten Canadians (72%) the answer to this existential question about the nature of poverty is the latter. A similarly large majority (65%) takes this perspective on the nature of wealth, saying rich people are rich because they had more advantages in life than most other people:

These two questions were based on ones previously asked by Pew Research in the United States, which found Americans considerably more divided – largely along political lines – over the reasons for a person’s wealth or lack thereof.

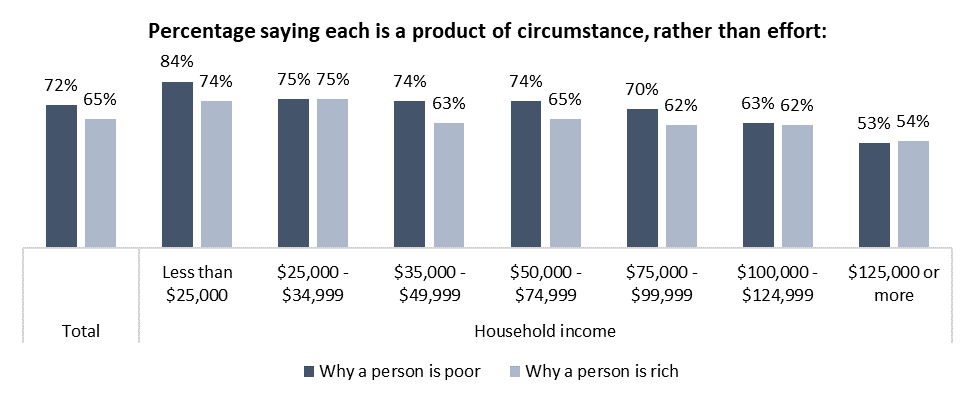

The belief that relative wealth or poverty is a product of circumstance, rather than individual effort, is a broad societal consensus in Canada. Solid majorities across regions, age groups, and genders feel this way (see comprehensive tables for greater detail).

Only two demographic groups are more divided in their responses to these two questions: Those with high household incomes and those who cast ballots for the Conservative Party in the 2015 federal election. Those with incomes of $125,000 or higher are much more evenly split on the origins of richness and poorness than those in lower income brackets:

Past CPC voters, meanwhile, are divided on this subject in a way that past Liberals and New Democrats are not:

Similarly broad coalitions of Canadians share other attitudes about poverty and wealth canvassed in this survey. Nearly nine-in-ten Canadians (88%), for example, agree that “providing a sense of human dignity is a critical part” of social service programs, and more than eight-in-ten (82%) agree that “the growing gap between the rich and everybody else is unacceptable.”

Likewise, three-quarters disagree with the notion that “people are poor because they’re lazy.”

These and other widely held attitudes are summarized in the graph that follows. For greater detail, see comprehensive tables.

Two other statements are more divisive, with roughly even numbers of Canadians agreeing and disagreeing. Not coincidentally, both of these statements asked respondents to weigh in on specific means of alleviating poverty, rather than simply assessing the current reality.

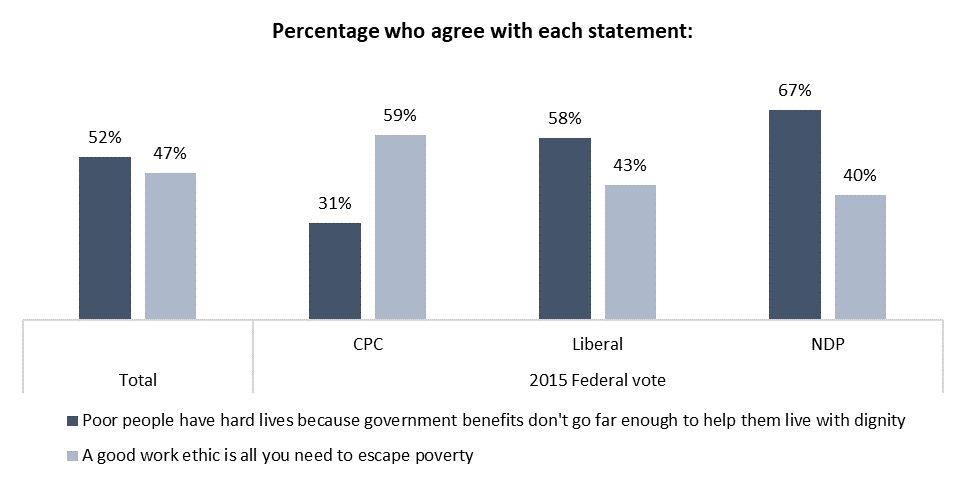

Roughly half of Canadians (52%) agree that “poor people have hard lives because government benefits don’t go far enough to help them live with dignity,” and nearly as many (47%) agree that “a good work ethic is all you need to escape poverty.”

Again, income and political partisanship are key drivers of divergence of opinion on these questions. Those with lower household incomes are especially likely to agree that government benefits don’t go far enough, while the highest income bracket is the only one in which a majority agree that poverty can be escaped through a good work-ethic and nothing more (see income tables).

In a similar vein, past Conservative voters largely disagree that government benefits don’t go far enough (69% do) and agree that a good work ethic is all one needs to escape poverty (59%), while majorities of those who supported the Liberals and New Democrats in 2015 take the opposite positions.

Interesting, if less dramatic, variation in Canadians’ responses to these two statements can be seen across regional, age, and gender lines as well. Women – especially young women – as well as British Columbians, Quebecers, and Atlantic Canadians tend to be more sympathetic to the argument that government benefits don’t go far enough (see comprehensive tables)

Attitudes across the lived experience segments

The first chapter of this report sorted Canadians into four groups based on their personal histories with economic hardship. Those groups, which are described in much greater detail in Chapter 1, are:

- The Struggling (16% of the general population), who have experienced numerous instances of deprivation in their lives, including at least one on an ongoing basis

- The On the Edge (11%), who have, on average, experienced fewer of the 12 situations asked about in the survey, and are more likely to have begun experiencing them only recently, rather than continuously throughout their lives

- The Recently Comfortable (36%), who all have at least some experience with the kinds of economic hardship canvassed, but usually only in the past or on an occasional basis

- And the Always Comfortable (37%), the vast majority of whom have no experience whatsoever with any of the 12 scenarios asked about

Underlining the degree to which certain attitudes toward poverty are the subject of a broad consensus in Canada today, these four segments offer fairly consistent views on why a person is poor or rich, and on the various agree/disagree statements asked about in this study.

As seen in the following table, the Always Comfortable are more likely than other segments to attribute a rich person’s wealth to that person working harder than others, but it is still a minority (44%) who feel this way. On the question of why a person is poor, the difference between groups become even less pronounced:

As is the case across demographic groupings, there are several attitudes that are shared across the four lived-experience groupings. On the two more divisive statements, the segments diverge, especially on the question of whether government benefits are sufficient:

Unacceptable or a fact of life?

As discussed at the end of Chapter 1 of this report, fully half of all Canadians (52%) believe the number of people living in poverty in their communities has been increasing in recent years. Fewer than one-in-ten (9%) say the number of people living in poverty near them has been on the decline.

These findings challenge the traditional, income-based measures of poverty in Canada, which have shown the number of Canadians living in low-income households remaining fairly consistent since the year 2000. Clearly, there is a disconnect between official statistics about income in Canada and the way Canadians perceive poverty in the world around them:

Looking beyond the relative perceived prevalence of each of these situations in Canada today, this survey asked respondents how willing they are to live with each one in their own communities. Is it acceptable – in a country as wealthy as Canada – for these circumstances that Canadians identify as fairly common to exist?

Respondents were shown the same list of circumstances and asked, for each one, which of the following perspectives is closer to their own:

“It is regrettable people nearby are experiencing this, but also a fact of life we need to accept,” or “It is unacceptable that people nearby are experiencing this, and something should be done about it.”

Notably, Canadians across the spectrum of lived experience tend to agree with one another on the relative acceptability – or lack thereof – of each item on this list:

While Canadians tend to hold similar views of these situations across all demographic groups, women are consistently more likely than men to view each item on the list as “unacceptable.”

Are governments doing enough?

Canadians perceive economic hardship everywhere. Even if they haven’t experienced it firsthand, they see it in their local communities. They see poverty as more commonplace than government statistics would suggest; they see it getting worse, not better; and they believe something needs to be done about all but the most minor economic struggles being experienced where they live.

Against this backdrop, it’s not surprising that the majority of Canadians believe their federal and provincial governments are doing too little to address poverty and assist people living in it.

The belief that Canada’s federal and provincial governments are not doing enough to address poverty is at least the plurality – and more often the majority – view across all demographic and income groups, as well as across the four segments of the lived experience spectrum.

Some people – particularly those with high household incomes and those who voted for the Conservatives in the 2015 federal election – are more likely than comparable groups to say that governments are doing too much, but they’re always outnumbered by those among their ranks who say governments are doing too little.

Similarly, some groups – particularly those in the Struggling and On the Edge segments, as well as those with low household incomes – are more likely than comparable demographics to say governments are doing too little. See the following graph and comprehensive tables for greater detail.

These findings amount to another broad consensus in Canadians’ attitudes toward poverty: That current government efforts to alleviate it are insufficient.

But what sort of additional efforts should Canadian governments be making? A related question in this study framed the notion of government intervention to address poverty through a more ideological lens, without tying the question to any sitting government.

Respondents were asked to choose between two opposing statements about poverty: Should there be “more public support for the poor, the disadvantaged and those in economic trouble” or “more emphasis on a system that rewards hard work and initiative.”

On this more-philosophical question, Canadians are split, with 52 per cent choosing the former option, and 48 per cent the latter. This is essentially unchanged from the last time the Angus Reid Institute asked this question in 2016.

Related: What makes us Canadian? A study of values, beliefs, priorities and identity

Those who are Struggling or On the Edge tend to favour the “more public support” option, while those in the two Comfortable segments are more evenly divided:

This question also generates significant regional and partisan differences, with past Conservative voters and Prairie residents more likely to favour emphasizing hard work, while past Liberals and New Democrats, as well as Quebecers, British Columbians, and Atlantic Canadians, prefer more public support for the poor:

Strong support for expanded governmental intervention

While the primary focus of this research was to identify those experiencing economic hardship in Canada today and determine how such experiences change peoples’ views of poverty, if at all, this survey also included a brief look at potential government interventions to address poverty. Further research is needed to understand what sorts of trade-offs – whether in the form of higher taxes or cuts to other spending areas – Canadians would be willing to make to support these interventions.

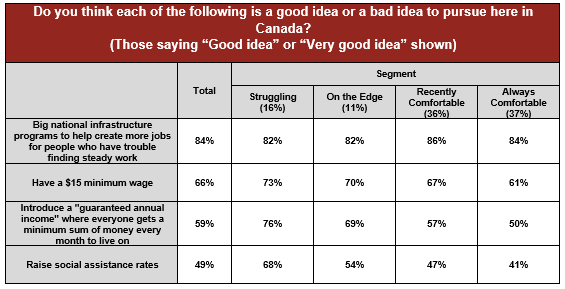

Of the four items canvassed, the most popular is the concept of “big national infrastructure programs to help create more jobs” for people who need them, which more than eight-in-ten Canadians (84%) see as a “good idea.”

Raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour and introducing a guaranteed annual income are also widely seen as good ideas, while Canadians are more divided on increasing social assistance spending:

More than four-in-five in each of the four segments of the experience spectrum also say a big national infrastructure program aimed at creating jobs is a good idea.

The other programs asked about in this survey are more controversial. While more than six-in-ten across each of the segments support having a $15 minimum wage, the Comfortable segments are much less enthusiastic about raising social assistance rates or introducing a basic income program, as seen in the table that follows.

On the topic of guaranteed income, past Angus Reid Institute research has shown that Canadians are broadly supportive of the concept, but most don’t think the federal government could afford to implement such a program, nor would they be willing to pay higher taxes to support it.

Related: Basic Income? Basically unaffordable, say most Canadians

Each of the non-infrastructure programs on this list enjoys substantially less support from past Conservative voters in comparison to those who supported other parties in 2015:

Notes on methodology

The four groups discussed in this survey are the result of an index based on the two-part lived experience question asked in this survey. Respondents were scored based on their answers to 10 of the 12 scenarios (all of the scenarios on the list except for “don’t have the money to go to a movie or similar outing” and “can’t afford to go out for dinner for a special occasion”).

Respondents who said they had not experienced an item received 5 points and were not asked the follow-up question about how frequently the scenario had occurred in their lives. Those who had experienced an item were scored based on their responses to the follow-up question, receiving 1 point if they said the experience was “ongoing in my life,” 2 points if the experience took place “from time to time,” 3 points if the experience was “more recent,” and 4 points if the experience happened “long ago” and has not happened since.

Adding up these scores yielded a total score for each respondent, ranging from 10 (all items “ongoing in my life”) to 50 (no to all items). The four segments correspond to four segments of this range. Those scoring 10 – 35 are the Struggling, those scoring 36 – 40 are On the Edge, those scoring 41 – 49 are the Recently Comfortable, and those scoring 50 are the Always Comfortable.

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist, Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and its world.

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics, click here.

For detailed results by household income, click here.

For detailed results by the four segments, click here.

Click here for the full report including tables and methodology

Click here for the questionnaire used in this survey

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Shachi Kurl, Executive Director: 604.908.1693 shachi.kurl@angusreid.org @shachikurl

Ian Holliday, Research Associate: 604.442.3312 ian.holliday@angusreid.org

Image Credit – Photo 190351564 © Ritaanisimova | Dreamstime.com