Divergent bilingualism, linguistic anxieties, and Bill 96

by David Korzinski | October 7, 2021 7:30 pm

A report by the Angus Reid Institute

October 8, 2021 – Language has long been understood as central to both personal and cultural identities. While home to many different immigrant and Indigenous languages, Canada’s linguistic identity is often approached through the lenses offered by its English and French speaking populations. Not confined to history, these conversations about language remain salient today and play out in both provincial and federal politics. This report from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute engages with these questions from a number of different angles. Specifically, it explores the future of bilingualism in Canada, concerns over the fate of the French language in Quebec, and the debate surrounding Bill 96—the proposed revision of Quebec’s language laws.

Key Findings:

- While two thirds (67%) say they are proud Canada is a bilingual country, it appears that francophones are far more bilingual in practice. Half (55%) of francophones across Canada say they are advanced to fluent in English whereas only 9 per cent of anglophones outside of Quebec report the same about French.

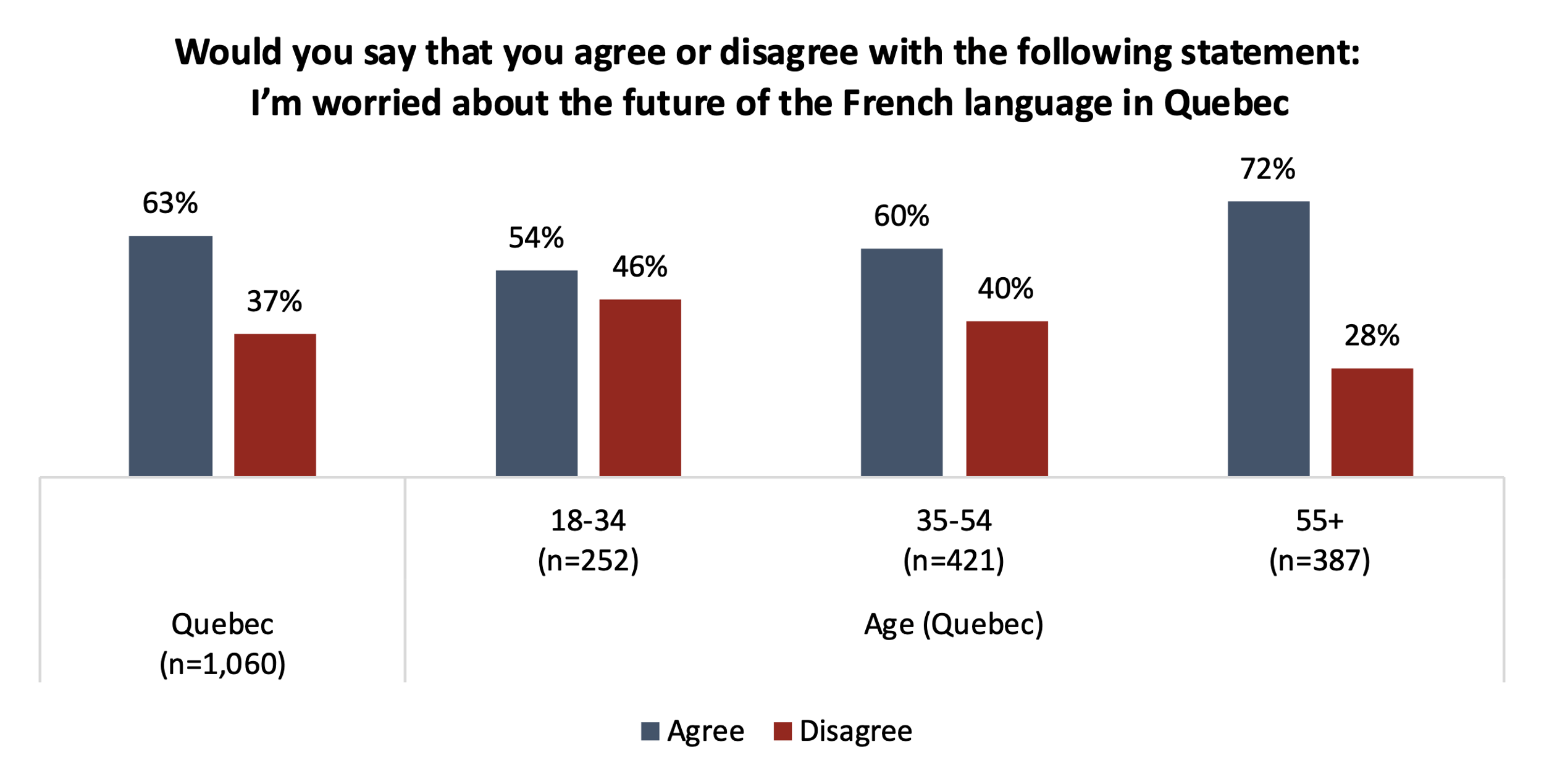

- While six-in-ten (63%) Quebecers say they are worried about the future of French in the province, this hides sharp linguistic divides. Three quarters (77%) of francophones agree that they are worried about the future of the French language in Quebec whereas nine-in-ten anglophones say they are not worried.

- When it comes to Bill 96, a proposed review of language laws in Quebec, six-in-ten (62%) Quebecers either support or strongly support it—a number which rises to three quarters (77%) of francophones in the province. In contrast, 95 per cent of anglophones in Quebec oppose the proposed bill.

- Although there was not much previous knowledge of Bill 96 outside of Quebec, nine-in-ten (89%) of those in the rest of Canada say they oppose the proposed bill.

- A copy of the full report can be found here[1]. Le rapport est également disponible en français[2].

About ARI

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting, and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research, and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and the world.

INDEX

Part One: The Status of official bilingualism in Canada

-

Understanding language proficiency

-

The linguistic lay of the land

Part Two: Linguistic anxieties

-

The future of the French language in Quebec and Canada

-

The future of English in Canada

Part Three: Bill 96: An act representing French, the Official and Common Language of Québec

-

Bill 96 and the path forward

Part Four: The view from the rest of Canada

Part Five: Canada’s two linguistic solitudes?

The status of official bilingualism in Canada

Even prior to Confederation Canada’s two official languages, English and French, were positioned at the heart of Canadian identity[3]. For a significant period of Canadian history there was a perceived lack of communication between these two linguistic and cultural communities—a breakdown in communication memorably captured in Hugh MacLennan’s novel Two Solitudes[4].

Since then, there have been several government policies designed to bridge these divides, notably by promoting French-English bilingualism. While official bilingualism in the Canadian context refers to a broad swathe of initiatives aimed at promoting proficiency in both languages, one of the cornerstones is the Official Languages Act (1969)[5] which requires all federal institutions to provide services in English and French upon request.

Recent data suggests that two-thirds (67%) of Canadians now find that French-English bilingualism is something to be proud of—albeit with important regional variations:

Understanding language proficiency

If Canadians are broadly supportive of official bilingualism in principle, the data from this survey suggests that the number who put this into practice and learn both official languages to a high degree of proficiency is far lower.

In order to understand the linguistic profile of respondents, this study adopted two approaches. The first was to ask which language(s) respondents learned and spoke first as a child. The second was to ask respondents to self-report their ability to speak, write, and understand either English, French, or both. The thresholds of proficiency were designed to correspond to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR)[6].Those with at least some knowledge of either French or English were divided into four levels:

- Fluent (CEFR C2): You can easily express yourself in detail on a wide range of subjects (e.g., literature, philosophy etc.)

- Advanced (CEFR B2): You can engage with complex ideas, but with some effort (e.g., technical discussions about your job, etc.)

- Intermediate (CEFR B1): You can handle conversations about familiar topics (e.g., work, travel, etc.)

- Beginner (CEFR A1): You can get by doing simple tasks (e.g., shopping, ordering food, etc.)

While the government of Canada uses a similar coding scheme[7] to qualify the linguistic proficiency of its employees, the Canadian census[8] only asks whether or not respondents are able to conduct a conversation in either official language.

The linguistic lay of the land

This study suggests that the linguistic lay of the land looks very different depending on the official language in question. Over half (51%) of francophone Quebecers would consider themselves advanced to fluent in English, while another two-in-five (46%) say they have either a basic or intermediate knowledge. Only three per cent say they cannot speak English at all.

Among allophones[9]—a term used to describe someone whose first language is not English, French, or an Indigenous language—English uptake is even higher. Eight-in-ten (79%) allophones in Quebec, and nine-in-ten (96%) in the rest of Canada, say that they are advanced to fluent in English (see detailed tables).

It is worth noting that, as the survey was only available in English and French, the number of allophones with no knowledge of either language is likely underreported.

The picture is very different when it comes to levels of proficiency in French across the country. Among those learning French as a second language, only eight per cent of Canadians outside of Quebec consider themselves advanced to fluent. Half (45%) say they have no proficiency in French whatsoever. The one exception is non-Francophones in Quebec, of which half (56%) consider themselves either advanced or fluent.

This data suggests that, in practice, Canadian bilingualism is driven by French Canadians learning English—a trend which Statistics Canada notes can be traced back to 1961[10]. A parallel trend, driven by the expansion of programs such as French immersion, does however suggest that younger generations of non-francophones are achieving higher levels of fluency (and retaining it better than older generations[11]):

A similar pattern is observed in francophone populations but to a greater extent:

This picture of divergent bilingualism complicates received truths about Canadian identity. If the idea of official bilingualism is often framed as central to what it means to be Canadian[12], it is interesting to note that those who feel the least attachment to the country—only 58 per cent of Quebecers say they have a “deep emotional attachment to Canada” (see detailed tables)—are those who are driving its expansion.

A side-by-side comparison reveals the full extent of this divergence:

Linguistic anxieties

This picture of divergent bilingualism takes on new meaning when placed in the historical context of centuries of language policies geared towards assimilating what was—especially for early colonial administrators—the “French problem.”

A report[13] presented by Lord Durham to the British government in 1839, for example, called for the immediate assimilation of French speakers—a people who he said had “no literature and no history”—into English speaking British North America. Although the Constitution Act, 1867 laid out that English and French were the official languages of the Canadian Parliament, policies which unfairly targeted French speakers persisted well into the 20th century (especially surrounding access to French schooling[14] in English majority provinces).

The future of the French language in Quebec and Canada

While these assimilationist policies were unsuccessful in the face of la survivance[15], there is a longstanding concern within French-Canadian communities surrounding the future of the French language in the country. In recent years these concerns have been fuelled by data[16] from Statistics Canada which shows that the proportion of those who speak French as a first language has steadily declined from 29.3 per cent in 1941 to 21 per cent in 2016 (it’s worth noting that the share of English as a first language also shrank due to the rise in those who speak non-official languages).

This decline of French in Canada, it is argued[17], is mirrored within Quebec as other languages (including but not limited to English) become more common at home and in the workplace. Within Quebec, this concern is divided along linguistic lines with three-quarters (77%) of first-language French speakers reporting that they are worried about the future of the French language in the province. By contrast, only half (55%) of those who grew up speaking both official languages are worried, whereas nine-in-ten (91%) English speakers in the province see nothing to be concerned about.

While not as acute as the linguistic divide, there are noticeable generational differences. Only half (54%) of Quebecers aged 18 to 34 are concerned about the future of the French language, compared with seven-in-ten (72%) of those over the age of 55.

There is also a strong geographic element to this discussion, with the expansion of English in Montreal often framed as at the heart of the problem[18]. Home to 80.5 per cent of Quebec’s anglophone population[19] and the primary immigrant-receiving city in the province, it tracks that half (53%) of those living in Montreal report noticing more English being used in their neighbourhood.

That being said, those in Montreal report being the least concerned about the future of French despite the perceived growth of English in the city. It is worth further noting that the regions of Quebec most concerned about the future of the French language—central and eastern Quebec, including notably Quebec City—are also those least likely to notice an increase in English being spoken in their neighbourhood:

The future of English in Quebec

If anglophones are not concerned about the future of the French language in Quebec, it seems a similar argument could be made about francophone opinions about the status of English in the province. Specifically, two-thirds (66%) of francophones believe that the rights of English speakers are already adequately protected in Quebec. In contrast, four-in-five (84%) who spoke English as their first language don’t agree.

Here again history provides important context clues. Provincial legislation in Quebec has imposed a number of restrictions on the conditions under which services in English can be accessed[20]. These affect a number of areas ranging from workplace restrictions to public signage. Restrictions on who can attend school in English have, for example, contributed to a decline in enrollment[21] from 200,000 pupils in the 1970s to fewer than 100,000 by 2008.

While these restrictions were framed by the provincial governments who introduced them as essential to the protection of the French language, the anglophone minority in Quebec has tended to perceive these as attacks upon their rights[22]—especially in instances where the notwithstanding clause[23] is invoked, effectively prohibiting any legal recourse to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Bill 96: An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec

In 1968 a royal inquiry commission[24] was set up by the federal government to address the inequality between the English and French languages as well as the lack of measures taken by the federal state to encourage the development of the French language. The Gendron Commission, as it came to be called, found strong evidence of a creeping Anglicisation of Quebec, a marginalisation of francophone Quebecers, and eventually proposed a series of recommendations to protect the future of the French language and its speakers.

The recommendations proposed by the Commission would lead the provincial Liberal government in Quebec to adopt the Official Language Act[25] in 1974 which made French the language of civic administration, services, and workplaces. This was followed in 1977 by the Charte de la langue française[26] introduced by the pro-independence Parti Québécois, which further strengthened these measures and made schooling in French mandatory for all immigrants (including those from elsewhere in Canada). The Charte de la langue française and its subsequent amendments were protested[27] by anglophones in Quebec.

As laid out above, concerns over the future of the French language in Quebec persist today. The most recent legislative initiative to protect the French language is An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec[28], more commonly known as Bill 96. Introduced by the Coalition Avenir Québec government, a newly formed centre-right party which seeks to pursue increased autonomy for Quebec, Bill 96 states that “Quebec is a nation and its official language is French.” Support for this symbolic measure is sharply split along linguistic lines:

In addition to this largely symbolic point, Bill 96 proposes a range of new measures which it deems necessary to protect and strengthen the French language in the province. Support for these proposed policies vary widely both by the measure and the linguistic community in question. While almost everyone agrees on providing free French classes (98 and 92 per cent of francophones and anglophones respectively), the linguistic divides are substantial on all other questions asked (for a full breakdown, see the detailed tables):

Francophones, if broadly supportive of these measures, are least convinced of those which impact their ability to access educational opportunities in English. This is especially notable when broken down by generation. When it comes to capping the number of spots available to francophone students in English language cégeps—publicly funded colleges in Quebec—half (50-52%) of francophones aged 18 to 54 oppose it, while seven-in-ten (71%) francophones over the age of 55 support it.

There is even less support for the proposed plan to reduce access to English-language programs in French cégeps, with two-thirds (64%) of francophones aged 18 to 34 and half (55%) of those between the ages of 35 and 54 coming out against it. Three-in-five (62%) francophones over 55, for their part, support it:

When asked about overall levels of support for Bill 96, it remains relatively flat across educational attainment, household income, and gender but differs significantly by generation—half (55-56%) of those aged 18 to 54 are in support compared to seven-in-ten (72%) of those over the age of 55 (see detailed tables). The sharpest divides, however, are again along linguistic lines:

There is, furthermore, an interesting correlation between proficiency in English and support for Bill 96—the more fluent one is in English it would appear the less likely they are to support it:

Bill 96 and the path forward

Despite some hesitancy surrounding specific proposed measures, francophones appear to be broadly sympathetic with the general idea underlying Bill 96: the protection of the French language in Quebec. Controversies aside, the legislative precursor to Bill 96, Bill 101, appears to have succeeded in encouraging the usage of French along some measures[29] such as the number of anglophone and allophone students attending French schools.

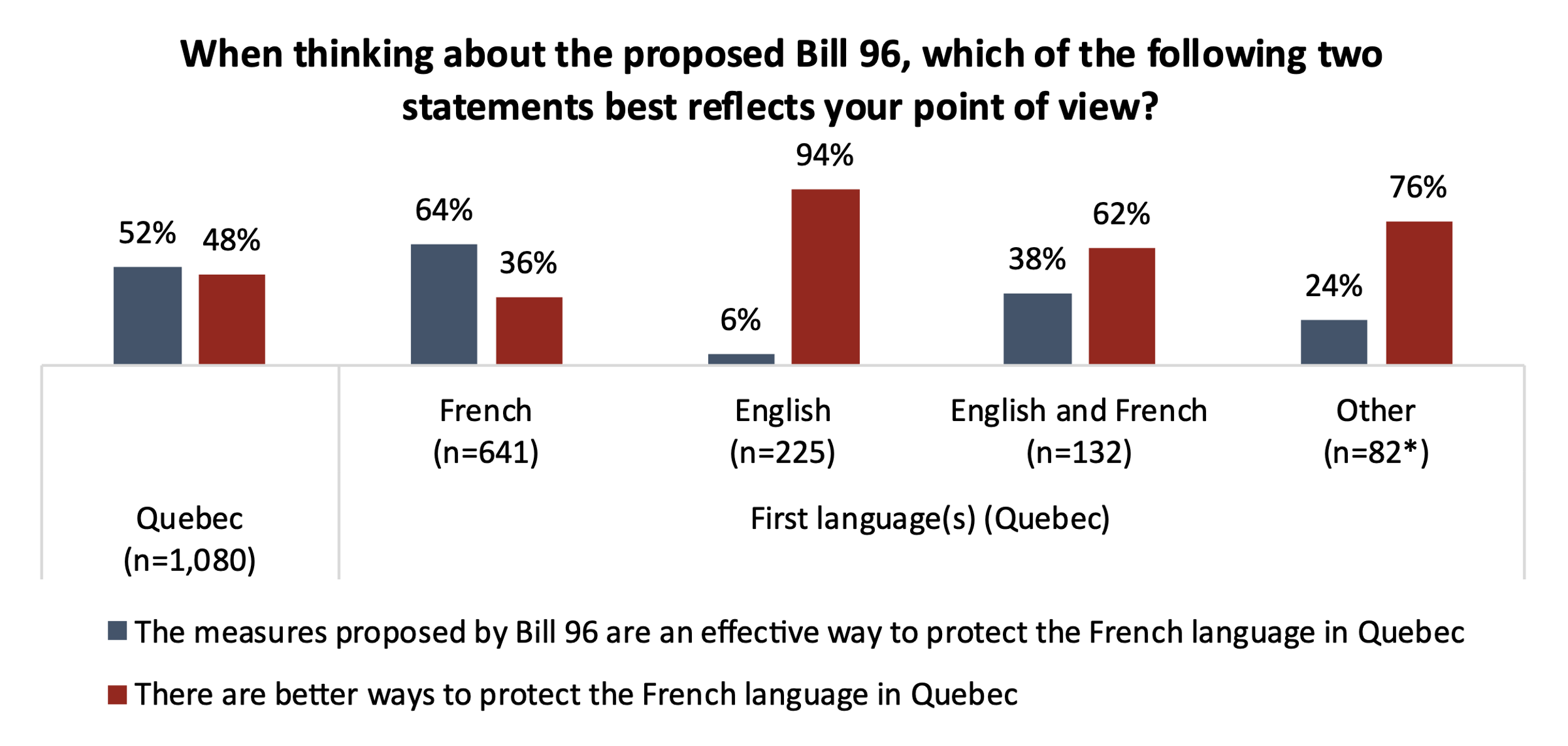

On the question of whether Bill 96 will be an effective addition to the legislative bulwark erected to protect the French language, the jury is still out. One-third (36%) of Quebecers who grew up speaking French as their first language say there are better ways of protecting the language. When looking at all of Quebec, this number rises to half (48%).

Paralleling the findings above, among non-anglophones the more fluent one is in English the more likely they are to think that there are better ways to protect the French language. Over half (55%) of those who consider themselves fluent in English think there are better ways to support the French language, compared with only one-in-five (21%) who rank themselves as a beginner (see detailed tables).

Overall, respondents expressed doubts about the potential implications of the bill. While those who think the impact will be positive are largely concentrated among French speakers and older generations (see detailed tables), a representative sample of all of Quebec suggests that there is significant concern about potentially negative impacts of Bill 96.

Three-in-five (62%) of all Quebecers believe that, if Bill 96 were to become law, that it would have a negative impact on the province’s reputation in the rest of Canada. Beyond reputational damage, a plurality of Quebecers (52%) are concerned this will negatively impact the willingness of commercial ventures to establish operations in the province and that it will have negative impact on industries based in Quebec (44%). Of note, there is no measure in which those who think the impact will be positive surpasses the 50 per cent threshold:

Here, there are important linguistic divides, with francophones far more likely to forecast positive outcomes than non-francophones (for a breakdown by anglophones and allophones see detailed tables):

In addition to the implications for Quebec as a whole, respondents were asked what the impact of Bill 96 would be on a more personal level: i.e., the future economic wellbeing of their family. Again, important divides emerged by language with 71 per cent of anglophones saying that, if Bill 96 were to be implemented, that it would have a negative impact on their personal economic wellbeing:

On this question older generations of francophones remain the most convinced that it will have a positive impact (47%), while the same number (46%) of those aged 18 to 34 believe it will have no impact on them at all (see detailed tables).

The view from the rest of Canada

The debates leading up to the passage of Bill 101 in 1977 were closely followed both within Quebec and outside, as were the years of controversy that ensued. While commentators have summoned the ghosts of Bill 101 to warn that Bill 96 might unsettle the linguistic peace in Quebec[30], it appears most outside of Quebec were not aware of what was happening—at least as of July this year. When asked how closely they were following Bill 96 in the news, only five per cent say they were actively doing so while two-in-five (43%) respondents outside of Quebec had never heard of Bill 96 before.

Though few outside of Quebec were aware of Bill 96 prior to this study, most appear to have been quick to form an opinion. Overall, there is strong opposition from the rest of Canada, with nine out of ten (89%) coming out against it. Notably, this opposition remains relatively consistent no matter one’s previous exposure to Bill 96:

In stark contrast with how most Canadians outside of Quebec feel about the proposed bill, all federal parties voted in favour of a motion introduced to parliament by the Bloc Québécois[31] which supports Quebec’s plan to amend the Canadian constitution to declare French as its only official and common language. Of the Members of Parliament present, all except two—both independents—voted in favour of the motion.

Although the opposition doesn’t reach quite the same heights as it does for Bill 96 itself, three-quarters (73%) of Canadians outside of Quebec oppose the Parliament’s decision:

Canada’s two linguistic solitudes?

To what extent have federal policies promoting bilingualism and communication across linguistic communities succeeded in overcoming Canada’s linguistic solitudes? Was then Governor General Michaëlle Jean right when, in 2005, she declared[32] that “the time of two solitudes, that for too long described the character of this country, is past”?

By some measures improvements have certainly been made. As mentioned at the beginning, there is broad support for the idea of bilingualism across the country and, while there are important differences between Quebec and the rest of Canada, younger generations appear to be increasingly bilingual. And yet, as the debate surrounding the decline of the French language and legislative measures such as Bill 96 illustrates, linguistic divides remain.

More than highlighting distinct views on the merits of Bill 96, the data here speaks to the ways in which French speakers see themselves within Canada, and the way English communities see their position within Quebec. The one area of overlap between these two narratives is that they both see themselves as at risk of decline. On one hand, Quebec—and francophone communities across Canada—are very much linguistic islands in a sea of English. On the other, the anglophone community is itself a minority nested within a larger linguistic community.

Ultimately, when framed by the contrasting narratives built around each community, whether Bill 96 offers promise or peril varies dramatically depending on where you’re standing. This much is reflected in how different linguistic communities perceive the intent of Bill 96. For four-in-five (80%) of those whose first language is French, it is a much-needed levee to protect the future of the French language against the rising tide of English. For nine-in-ten (91%) who spoke English as their first language, it is instead a legislative attack against their community.

Of course, missing in both these narratives are the experiences of allophones and Indigenous peoples—both of which it could be argued are overlooked when Canadian history is construed as one built on two linguistic solitudes. Indeed, as the leader of the Kanesatake Mohawk community in Quebec pointed out earlier this summer[33], Indigenous peoples understand all too well what it means to have to fight for your language and culture when surrounded by a much larger population.

The larger issues of framing Canadian history as one of two solitudes notwithstanding, the data here suggests that, despite the many similarities in their narrative arcs, important differences remain. At least in this instance, it would appear that elements of Canada’s linguistic solitudes linger on. Going forward it remains to be seen if legislative efforts such as Bill 96 and the federal government’s new policy aimed at promoting linguistic equality[34] can succeed in bridging these divides or not.

Methodology

The Angus Reid Institute conducted an online survey from July 25 to 29, 2021, among a representative randomized sample of 2,103 Canadian adults who are members of Angus[35] Reid Forum.

For comparison purposes only, a probability sample of this size would carry a margin of error of +/- 2.1 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. Discrepancies in or between totals are due to rounding.

This included both an augmented survey sample of 1,080 respondents from Quebec, as well as augments of anglophone and allophone Quebecers which brought these key survey sub-samples to 225 and 82 respondents respectively. Throughout the study sample sizes labelled Canada, Quebec, or Rest of Canada (ROC) are weighted to be representative. Regional and linguistic community sample sizes are unweighted.

The survey was self-commissioned and paid for by ARI. Detailed tables are found at the end of this release.

To read the full report, including detailed tables and methodology, click here[1]. Le rapport est aussi disponible en français[2].

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics in Canada click here[36].

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics in Quebec click here[37].

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics in the rest of Canada click here[38].

For full questionnaire, click here[39].

Image – Adrien Olichon/Unsplash

Media Contact

Shachi Kurl, President: 604.908.1693 shachi.kurl@angusreid.org[40] @shachikurl

Angus Reid, Chairman: angus.reid@angusreid.org[41] @angusreid

Gregor Sharp, Senior Research Associate: gregor.sharp@angusreid.org[42]

- here: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.08.13_Bill_96_Report_ENG.pdf

- en français: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.08.13_Bill_96_Report_FR.pdf

- heart of Canadian identity: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2016001-eng.htm

- Two Solitudes: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/two-solitudes

- Official Languages Act (1969): https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/official-languages-act-1969

- Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR): https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/level-descriptions

- coding scheme: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/staffing/qualification-standards/relation-official-languages.html#second

- census: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2016/ref/questionnaires/questions-eng.cfm

- allophones: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/allophone#:~:text=Languages%20in%20Canada).-,In%20Canada%2C%20allophone%20is%20a%20term%20that%20describes%20a%20person,see%20Immigrant%20Languages%20in%20Canada).

- can be traced back to 1961: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2019001/article/00014-eng.htm

- retaining it better than older generations: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2019001/article/00014-eng.htm

- often framed as central to what it means to be Canadian: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-identity-and-language

- report: https://primarydocuments.ca/report-on-the-affairs-of-british-north-america-durham-report/

- access to French schooling: https://www.tvo.org/article/why-ontario-once-tried-to-ban-french-in-schools

- la survivance: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/nationalisme-canadien-francais

- data: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2018001-eng.htm

- argued: https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/two-oqlf-studies-show-french-declining-in-quebec

- heart of the problem: https://www.journaldequebec.com/2020/11/20/declin-du-francais-a-montreal--on-va-perdre-le-controle-de-notre-langue-sinquiete-labeaume

- Quebec’s anglophone population: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/lang/lang-eng.htm

- conditions under which services in English can be accessed: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quebec-language-policy

- a decline in enrollment: http://danielturpqc.org/upload/The_Vitality_of_the_English-Speaking_Communities_of_Quebec.pdf

- attacks upon their rights: https://montrealgazette.com/opinion/editorials/editorial-a-time-for-english-speaking-quebecers-to-focus-on-our-future

- notwithstanding clause: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-notwithstanding-explainer-1.6065686

- royal inquiry commission: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/commission-of-inquiry-on-the-situation-of-the-french-language-and-linguistic-rights-in-quebec-gendron-commission

- Official Language Act: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/loi-22

- Charte de la langue française: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/loi-101

- protested: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/loi-101

- An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec: http://m.assnat.qc.ca/en/travaux-parlementaires/projets-loi/projet-loi-96-42-1.html

- along some measures: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-bill-101-40th-anniversary-1.4263253

- unsettle the linguistic peace in Quebec: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bill-96-quebec-language-laws-1.6025859

- motion introduced to parliament by the Bloc Québécois: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-parliament-passes-bloc-motion-supporting-quebecs-constitutional-plan/

- declared: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/time-of-two-solitudes-has-passed-jean/article20426310/

- pointed out earlier this summer: https://montrealgazette.com/news/quebec/quebecs-bill-96-is-a-second-colonization-kanesatake-grand-chief-says

- new policy aimed at promoting linguistic equality: https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/corporate/publications/general-publications/equality-official-languages.html

- Angus: http://www.angusreidforum.com

- here: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.09.30_Bill_96_Release_Tables_CAN.pdf

- here: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.09.30_Bill_96_Release_Tables_QC.pdf

- here: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.09.30_Bill_96_Release_Tables_ROC.pdf

- here: https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.07.21_Bill_96_Questionnaire_ENG.pdf

- shachi.kurl@angusreid.org: mailto:shachi.kurl@angusreid.org

- angus.reid@angusreid.org: mailto:angus.reid@angusreid.org

- gregor.sharp@angusreid.org: mailto:gregor.sharp@angusreid.org

Source URL: https://angusreid.org/bilingualism-french-bill-96/