A Portrait of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Canada today

Intersections between objective isolation and subjective loneliness divide the population into five groups

June 17, 2019 – Interpersonal connection is at the heart of all human society. As a species, we thrive on relationships and social interaction, to the point that our health as individuals is negatively affected in the absence of these connections.

A wide-ranging new study from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute, conducted in partnership with Cardus, explores the quality and quantity of human connection in the lives of Canadians today, revealing significant segments of society in need of the emotional, social and material benefits connectedness can bring.

Fully six-in-ten Canadians (62%) say they would like their friends and family to spend more time with them, while only 14 per cent of Canadians would describe the current state of their social lives as “very good.”

Further, a substantial one-third (33%) could not definitively say they have friends or family members they could count on to provide financial assistance in an emergency, and nearly one-in-five (18%) aren’t certain they’d have someone they could count on for emotional support during times of personal crisis.

This study sorts Canadians along two key dimensions: social isolation (or the number and frequency of interpersonal connections a person has) and loneliness (or their relative satisfaction with the quality of those connections).

From these and other findings, a detailed portrait of isolation and loneliness in Canada emerges, sorting Canadians into five groups: The Desolate (23%), the Lonely but not Isolated (10%), the Isolated but not Lonely (15%), the Moderately Connected (31%), and the Cherished (22%).

More Key Findings:

- The Cherished – those who suffer from neither social isolation nor loneliness – are most likely to be married, have children, and higher incomes.

- While income level plays a significant role in the lives of all Canadians, the experiences of Canadians 55-and-older are particularly noteworthy. Within this group, those with incomes of less than $50,000 are twice as likely to be found in the Desolate group than those with incomes of $100,000 or more

- Visible minorities, Indigenous Canadians, those with mobility challenges, and LGBTQ2 individuals are all noticeably more likely to deal with social isolation and loneliness than the general population average.

- Faith-based activities, such as praying, church attendance and community outreach, are correlated with less isolation for individuals who partake in them

- A strong majority of Canadians who use technology such as social media, texting, or video calling to remain connected with friends and family say that they appreciate the impact it has had on their ability to stay in touch

About ARI

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist, Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and its world.

INDEX:

Part 1: What are social isolation and loneliness?

-

Isolation vs. Loneliness

-

Measuring Social Isolation

-

Measuring Loneliness

Part 2: The Index of Loneliness and Social Isolation (ILSI)

-

Who fits where?

-

Income and education

-

Generational comparison

-

Household composition and companionship

-

Importance of children

-

Minority groups

-

Religiosity, Isolation, and Loneliness

Part 3: Key Takeaways from the ILSI

-

Quality of Interpersonal relationships

-

Negative effects of isolation and loneliness

-

Financial and emotional support

-

Community activity and belonging

Part 4: Solutions

-

Introvert or extrovert?

-

Does technology help?

-

Most want more time with friends and family

Part 1: What are social isolation and loneliness?

Isolation vs. Loneliness

In approaching the intersection of isolation and loneliness, one might think these phenomena are the same. However, someone dealing with social isolation could be described as a person with few social contacts, little meaningful interaction, or a lack of mutually rewarding relationships.

Isolation differs from loneliness in key ways. While isolation can be described through objective behaviours, such as actions and contact with others, loneliness is subjective. It is a feeling that permeates a significant level of the population.

Loneliness has been described as a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that a person has, compared with what a person wants. It is an unwelcome feeling of lacking companionship. One way to think about the distinction is that a person cannot be isolated in a crowded room, but a person could feel lonely in that same room.

While these two ideas are separate unto themselves, they can also be connected, and research suggests that one can sometimes lead into the other. Both of these issues have been described as a public health problem, as each can have negative health effects if they persist.

Measuring social isolation

To get a sense of the prevalence of social isolation in Canada today, the Angus Reid Institute asked respondents a variety of questions about their time spent with – and without – other people. Those questions included:

- How much time are you alone? (35% of Canadians say “often” or “always”)

- In the past month, how much social interaction have you had with:

-

- Other members of your household (Among those who live with at least one other person, – 51% do “all the time”)

- Co-workers/Other students (31% of those working or studying say daily or “many times” per month)

- Family members not living with you (20% say daily or many times per month)

- Friends (17% socialize with friends “frequently”)

- Your neighbours (7%)

- Have you ever spent a special occasion alone when you would have rather been with other people? (10% of Canadians say this “often” happens, 41% say it happens sometimes)

- Do you yourself ever do any of the following?

- Socialize with your neighbours (30% of Canadians say they do this regularly)

- Use the local community centre or library (23%)

- Go out to live events like music or theatre (21%)

- Volunteer for a community group or cause (18%)

- Participate in neighbourhood or community projects (8%)

On the surface, it appears that Canadians do not spend a significant portion of their time interacting with people outside of their own household. When asked how often in the past month they had seen various groups, from family members outside of their home, to friends, to neighbours, at least half in each instance say that none of these are a weekly occurrence for them:

Thus, people who live alone are at an acute disadvantage in terms of their social interactions. Because such a significant proportion of Canadians’ social stimulation comes from within their own homes, those who live alone are generally more isolated.

This is significant given that living alone is becoming increasingly common. The percentage of Canadians in single-person households has grown significantly over the past 25 years. Statistics Canada estimates that one-in-four (26%) Canadians over 65 live alone. Further, the total proportion of the population living in one-person households has quadrupled over the last three generations, growing from 7 per cent in 1951 to 28 per cent in 2016.

Thus, community engagement becomes increasingly important. However, Canadians are not particularly likely to be socially active in their immediate geographic communities. Just three-in-ten (30%) say they regularly socialize with their neighbours, while just one-in-five (18%) say they volunteer in their communities or go out to events such as live music or theatre shows (21%):

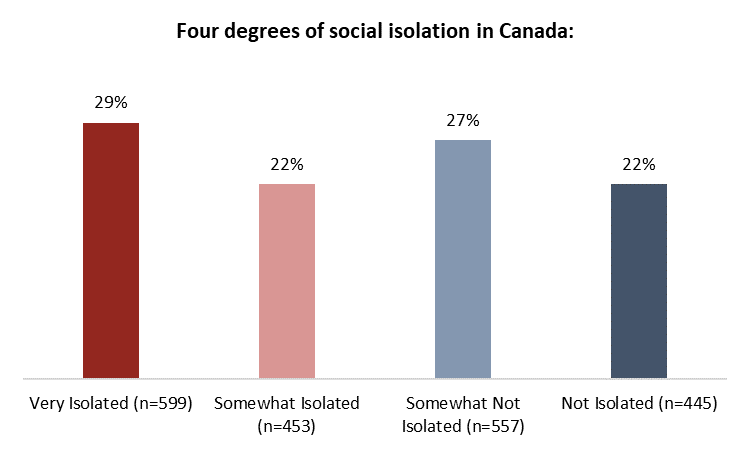

Combining the variables listed above, ARI researchers created a “social isolation index,” which grouped Canadians into the four categories below:

Measuring Loneliness

Similarly, the survey questionnaire asked respondents a series of questions aimed at measuring feelings of loneliness, including:

- How often do you:

- Wish you had someone to talk to, but don’t (41% of Canadians often or sometimes feel this way)

- Feel lonely and wish you had more friendly human contact (47%)

- Wish you had someone to go places with (54%)

- Good friends: enough or wish you had more? (35% say they wish they had more)

- Is the amount of time you spend alone about right, or would you change it? (23% would rather have less time alone)

- Do you wish your own family and friends would spend more time visiting and socializing with you? (62% of Canadians would like more time, including 15% who wish for “lots more”)

One notable pattern that emerges in responses to many of these questions is that women under 35 tend to express greater feelings of loneliness than other age groups.

For example, while four-in-ten Canadians (40%) say that they sometimes or often wish they had someone to talk to but don’t, this sentiment rises to six-in-ten among young women (59%):

Further, young women are also much more likely to feel alone when they’re with other people:

Another path to gauging loneliness is to consider how much time Canadians spend alone, and whether or not this is ideal for them. One of the key elements of loneliness is a person’s desired social life compared to their actual circumstances. Using this lens, one-quarter of Canadians (23%) say they would rather have less time alone, led by 18-34-year-olds:

Combining these variables yields the following four groups of Canadians when it comes to loneliness:

Part 2: The Index of Loneliness and Social Isolation (ILSI)

Who fits where?

In order to explore how these two concepts of social isolation and loneliness relate and overlap, the Angus Reid Institute first developed the two indices described in part 1 of this report – creating four categories based on social isolation and four based on loneliness.

Researchers then looked at a crosstab of the two indices to determine how many people in each of the four loneliness groups find themselves in each of the four isolation groups. How many people in Canada are Very Lonely but Not Isolated? How many are Very Isolated but Not Lonely? The graphic below shows the intersection of the eight groups and a colour coding of how they were further classified on ARI’s Index of Loneliness and Social Isolation (ILSI).

The five categories of the ILSI emerge as follows. For reference, the colours of the groupings below correspond to their place on the table above:

- The Desolate (n = 474, 23% of the total population): These people are both lonely and isolated, and they fit into at least one of the “very lonely” or “very isolated” groups.

- This group is more likely to be lower income: 41 per cent have an annual household income of less than $50,000.

- Half (48%) have a high school education or less, and they are evenly distributed by age.

- This group is also twice as likely as the Cherished to be single and to live alone.

- Notably, many minority groups, including visible minorities, LGBTQ2 individuals and Indigenous Canadians, are more likely to be found in this group than others.

- Lonely but Not Isolated (n = 199, 10% of the total population): This group is either very or somewhat lonely but finds itself in the non-isolated segments of the isolation index.

- This is the smallest and youngest group of the total population

- More than four-in-ten (43%) are under the age of 35, while just one-in-four (24%) are 55 or older.

- Their income levels mirror the national average, but this group scores highest on education with 33 per cent having studied at university.

- Fewer than six-in-ten (57%) are married or in a common law relationship, the lowest number except for the Desolate (48%)

- Isolated but Not Lonely (n = 299, 15%): This group is the reverse of the former, in which members of the very or somewhat isolated groups find themselves in the non-lonely segments of the loneliness index.

- These Canadians are characterized by lower than average income and education levels.

- This group skews older– half (48%) of its members are 55 or older.

- Six-in-ten (62%) are married, but many in this group have likely seen their children leave home.

- Half (48%) have children over the age of 18.

- The Moderately Connected (n = 639, 31% of the total population): These people are neither very lonely nor very isolated, but they also don’t display the characteristics of those who are not lonely or not isolated. They occupy a middle ground in this spectrum and tend to respond to questions in a way that mirrors the general population, overall.

- This group is perhaps characterized by its proximity to the image of the “average Canadian.”

- Income levels, education, age, household composition and marriage status are all remarkably similar to the national average.

- The Cherished (n = 444, 22% of the total population): This group is neither lonely nor isolated. Its members find themselves in at least one of the “not lonely” or “not isolated” groups.

- The group most well-off are the Cherished.

- These Canadians have higher than average household income levels

- They are most likely to be married (75% are).

- They are also the most likely to have children, and due to these two preceding items, are least likely to live alone (just 11% do).

Income and education

While each index group has members of all levels of wealth within it, The Desolate are twice as likely as The Cherished to have household incomes below $50,000 per year (41% vs. 21%).

Indeed, income level appears to rise across each of the five groups, from least connected to most, as seen in the graph below:

Further, The Desolate and the Isolated but Not Lonely are considerably less likely to have a university education, and much more likely to have a high school education or less, to the other groups. That said, this is more of a trend than a rule, as The Cherished are nearly evenly distributed across the three education levels:

Generational comparison

Age plays a key role in the discussion around social isolation and loneliness. This area of research is well canvassed with respect to seniors, who often report difficulties dealing with social isolation as they become more removed from friends or family after moves, or the loss of loved ones.

This, alongside potential mobility challenges and transportation limitations, may increase isolation among the aged. This trend is also seen in the ILSI, as those 55-and-older are considerably more likely to make up the Isolated but Not Lonely. That is, while they may not feel lonely, they have less positive interaction and contact with others than younger people.

That said, there is another group where those 55-and-older are overrepresented – the Cherished. So, while for some, the so-called “golden years” are a time of freedom and opportunity for connection, for others, they can represent hardship and personal challenges.

Young people, as mentioned earlier, are overrepresented in the Lonely but Not Isolated group. This suggests that some younger people are sufficiently engaged, but perhaps lacking in terms of their feeling of connection:

The difficulty for older Canadians becomes more evident when looking at this 55-and-older age group by income level. Seniors with lower incomes are much more highly represented in the Desolate group:

Household composition and companionship

How much does having housemates impact a person’s sense of loneliness? It does, and it doesn’t. Consider two findings: The Desolate are more likely to live in small households – either alone or with just one other person. However, fully half of the Lonely but Not Isolated (53%) live with at least three other people, but are still – by definition – lonely:

By contrast, marital status is more consistently correlated with people’s senses of connectedness. The Desolate and the Lonely but Not Isolated are considerably less likely to be married or have a common-law spouse. Those who are at least Moderately Connected are more likely to be married, as are those who are Isolated but Not Lonely.

This suggests that for many, a spouse or partner is a key source of comfort and support. This is most evident among The Cherished – the group most likely to be married or common-law.

Importance of children

The Desolate are less likely to have children, while those in the Isolated but Not Lonely and Cherished groups – each of which tends to be older than the general population – are more likely to have grown children. Younger children are most likely to be found in the homes of those who are Lonely but Not Isolated. These parents evidently have their hands full, but may feel unfulfilled at times in terms of the expectations they have for their social life and the reality they face:

Minority groups

Minorities in Canadian society tend to be over-represented in the Desolate category.

About one-in-six (16%) Canadians surveyed self identify as “visible minorities” – people whose ethnic or religious backgrounds mark them as noticeably different from the majority white, European-descended population. Visible minorities are slightly over-represented in The Desolate (30% are in this category), relative to those who do not self-identify as such (22%).

In a similar vein, the 7 per cent of respondents to this survey who identify themselves as Indigenous are more likely to be in the Desolate group (30% versus 23% of non-Indigenous respondents; see index tables for greater detail).

Those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or two-spirit (LGBTQ2) are significantly more likely to be in the Desolate group, and significantly less likely to be in the Cherished one, as seen in the graph that follows.

Physical disability is also highly correlated with more intense feelings of social isolation and loneliness. Nearly four-in-ten (38%) of those who have a physical disability are among the Desolate, as are more than one-in-four (27%) who have mobility challenges that affect their day to day lives:

Religiosity, Isolation, and Loneliness

Are there links between connectedness and faith or religious participation? Upon first glance, the relationship is not immediately illuminated, especially when viewed across the Angus Reid Institute’s Spectrum of Spirituality (read more about that here):

That said, Canadians who are more religiously active are less likely to experience isolation. This is observable by examining religious attendance and its relationship with the ILSI. The Desolate and the Isolated but Not Lonely are more likely than other groups to never or rarely attend religious services. So, the two groups experiencing the highest levels of isolation are also the least likely to participate in religious activities:

This pattern of religiosity and lower levels of isolation is even clearer when the loneliness component is removed from the equation. Those who are more isolated are much less likely to have regular experience with religious communities. The Not Isolated are, in fact, more than twice as likely as the those on the opposite end of the Isolation Index to regularly attend religious services.

Another component of faith, prayer, is also more common in groups that experience less isolation. Half of the Not Isolated say they pray monthly (51%), while the proportion of those who do diminishes across each of the subsequent, more isolated, groups:

Part 3: Key Takeaways from the ILSI

Quality of Interpersonal relationships

Importantly, a person’s place on The Index on Loneliness and Social Isolation (ILSI) correlates with elements of life satisfaction overall. For example, the Desolate are much more likely to assess their current social life negatively, while the Cherished almost unanimously see theirs as positive:

Satisfaction with the independent elements of one’s personal life are also highly correlated with their place on the ILSI. The number of the Cherished who say relationships in their lives are “very good” is well above the other four groups, while the proportion of the Desolate saying the same is consistently less than half that of the Cherished:

Negative effects of isolation and loneliness

Whether it’s finances, physical and mental health, or social life, in each case, significant gaps exist between those with more connected social infrastructures and those without:

Perhaps the starkest gap emerges on life satisfaction. Asked to rate their lives overall, six-in-ten (60%) among the Cherished say that they are “very satisfied.” This drops to 28 per cent among the Moderately Connected, and further, to just one-in-ten (12%) among the Desolate, as seen in the graph that follows.

Notably, a minority of Canadians are “very satisfied” with their lives. Just one-in-three (33%) say this:

Financial and emotional support

There are also material consequences to isolation and loneliness. Asked whether they feel they have someone to turn to in a time of serious financial trouble, more than half (54%) of the Desolate cannot say definitively that they would have someone. Conversely, at least six-in-ten across each of the other groups say they have at least one or two people they can think of to turn to in this situation.

Overall, fully one-in-three Canadians (33%) are uncertain whether they would be able to count on friends or family members in a financial emergency:

In a time of emotional need, nearly one-in-five Canadians (18%) couldn’t say for sure they have someone they could turn to. The proportion of the Desolate who say this is more than twice that number (41%):

On a related note, about half of Canadians (46%) say they have fulfilling face-to-face conversations on a regular basis. For another one-third (34%), these are intermittent. What stands out is the increased likelihood that The Desolate rarely or never have meaningful conversations in their lives:

Community activity and belonging

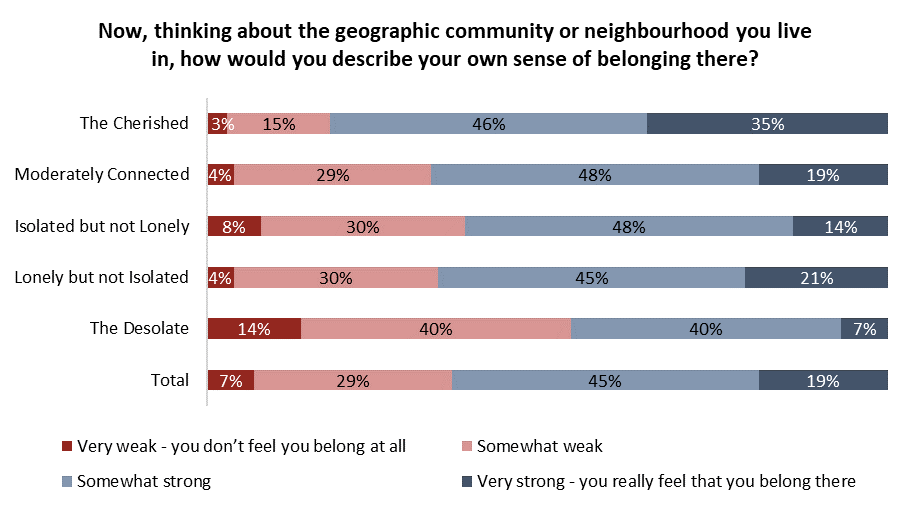

Does a lack of connectivity drive diminished feelings of belonging within one’s community? While two-thirds (64%) overall say they have at least a “somewhat strong” sense of belonging, for the Desolate, the pendulum swings the other way. They are the only group wherein a majority (54%) feels a weak connection to their immediate surroundings:

Part 4: Solutions

Introvert or extrovert?

This research has mostly dealt with issues of isolation and loneliness at the scale of Canada’s population as a whole, rather than within specific affected groups. Still, a significant proportion of the population may feel predisposed to reject efforts to increase the quantity and quality of their social interactions. More than seven-in-ten Canadians (71%) self-identify as introverts, rather than extroverts. Actual proportions of introversion or extroversion in Canada are difficult to pin down, and some Canadians may be a little of both, or “ambiverted.”

For many introverts, increased interpersonal contact isn’t necessarily positive or desirable. Members of the Isolated but not Lonely group, in particular, may not be clamouring for increased human contact. That said, each of the five segments of the ILSI also contains extroverted people who – with the possible exception of the Cherished – would likely enjoy and benefit from more and deeper relationships.

For those extroverted people who are not currently among the Cherished – and likely for many introverts as well – more frequent or higher quality human interaction would be a boon, and the starting point for any resolution to the problems of isolation and loneliness.

Does technology help?

One potential avenue for increased social interaction is technology. Most Canadians talk on the phone and use social media to keep in touch with friends and family at least occasionally, and this survey finds some four-in-ten (38%) adopting video calling applications for such communications as well:

Most people who use social media, text or email to keep in touch with friends and family say doing so makes them feel more connected, and an even greater share of those who use video calling say the same, as seen in the graph that follows. Very few Canadians who use these technologies for social interaction actively dislike them, though many are lukewarm, describing them as “better than nothing”:

Most want more time with friends and family

Spending more time with others in the physical world is an obvious remedy for social isolation, as well as loneliness, but Canadians’ willingness to actually spend more time with each other is difficult to measure.

On one level, Canadians seem acutely aware of loneliness in their social circles. Most (76%) say there are – or at least could be – people in their lives who are lonely and need more companionship. Just one-in-four (24%) don’t believe this is the case, though this perception varies significantly across the ILSI:

Despite their widespread recognition of loneliness in others, Canadians aren’t necessarily making a point of addressing it. Fewer than one-in-five (19%) of those who say they know someone who is lonely also regularly make a point of spending time visiting such a person:

And yet, most Canadians (62%) wish family and friends would spend more time with them. Indeed, one-in-six (15%) are wishing for “lots more” time with their own friends and family. This pattern holds true in three of the five segments.

Among the Desolate, one-in-three (33%) want “lots more” time and fully nine-in-ten (91%) want at least some more time with their friends and family. Similar proportions of the Lonely but not Isolated respond to this question in that way, while those in the Moderately Connected category are more divided (64% of them, overall, wish their friends and family spent more time with them).

It’s only those who are Isolated but not Lonely – reflecting their contentedness with being left alone – and those who are Cherished who are largely satisfied with the current amount of time they see others:

For detailed results by age, gender, region, education, and other demographics, click here.

For detailed results by The Index of Loneliness and Social Isolation (ILSI), click here.

Click here for the full report including tables and methodology

Click here for the questionnaire used in this survey

Image – Kristina Tripkovic/Unsplash

MEDIA CONTACT:

Dave Korzinski, Research Associate: 250.899.0821 dave.korzinski@angusreid.org