Bike lane divide: Canadians more likely to blame cyclists than drivers for conflict on the roads

Two-thirds say separated bike lanes are a good thing, but far fewer want more in their cities

June 28, 2018 – It’s a familiar debate in urban Canada: a city announces plans to build a dedicated bicycle lane on a major roadway and opponents – fearing loss of parking, loss of business access, or an increase in traffic congestion – attempt to apply the brakes. Cycling advocates, meanwhile, gear up their encouragement of the new lane, which they argue will make riding a bike safer and more accessible for novices.

Now, a new public opinion poll from the Angus Reid Institute finds most urban Canadians all for separated bike lanes in the abstract, but less-than-enthusiastic about building more of these lanes in their communities.

And while most Canadians say there isn’t much conflict between cyclists and drivers in the cities where they live, people who’ve borne witness to clashes between the two groups tend to blame those on two wheels, rather than those on four.

These findings come as the country’s largest city searches for ways to make its roads safer in the wake of a surge in pedestrian and cyclist deaths so far in 2018.

More Key Findings:

- Two-thirds of Canadians (67%) say too many cyclists in their communities don’t follow the rules of the road, and nearly the same number (64%) say too many drivers don’t pay enough attention to bicycles on the roadway

- Large majorities of both frequent drivers (64%) and frequent cyclists (85%) say separated bike lanes are a good thing, but there is a notable gap between the two groups on whether there is an adequate number of such lanes where they live

- Residents of the Vancouver, Edmonton, and Calgary metro areas are considerably more likely to say there are “too many” separated bike lanes where they live than those who live in other large cities across the country. One of these cities – Vancouver – has regularly been ranked among Canada’s “most bikeable,” while the other two have not

INDEX:

- More blame cyclists than drivers for conflict on the streets

- Mode of transport drives opinion

- How many separated bike lanes is too many?

- Most see separated bike lanes as a good thing overall

More blame cyclists than drivers for conflict on the streets

There’s been no shortage of argument over bikes and bike lanes in recent years, but most Canadians say they don’t see much conflict between cyclists and drivers where they live. Some six-in-ten offer this fairly easy-going assessment of the situation on the roads in their communities, with the remaining four-in-ten split between blaming cyclists and drivers for the “quite a bit” of conflict they perceive between the two camps:

City-dwellers – likely as a result of higher rates of cycling and more congested streets in their areas – tend to be to see more conflict than the national average. Overall, 43 per cent of urban residents see conflict where they live, compared to 57 per cent who do not, and the conflict number grows substantially in certain large metro areas.

Full majorities in Metro Vancouver, Winnipeg, and Halifax say there is quite a bit of conflict between cyclists and drivers in their area, as do six-in-ten residents of central Toronto’s 416 area code. Only in the more-suburban 905 area code is the perception of conflict lower than the national average:

Looking at only those respondents who say there is a feud between drivers and bicyclists where they live, the trend becomes clear: In most urban areas, those who perceive a conflict are inclined to say cyclists are to blame. The notable exceptions are Winnipeg and Halifax, where responses are split more evenly:

One’s age is also correlated with one’s views on whether drivers or cyclists are more responsible for conflict on the roads.

Canadians ages 55 and older who see quite a bit of disagreement between drivers and cyclists in their communities are more likely to take the driver’s side, blaming cyclists for the conflict by a three-to-one margin. Meanwhile, those under age 35 who see problems on their neighbourhood streets are fairly split on which group to blame, with slightly more than half (53%) blaming those in motor vehicles:

Mode of transport drives opinion

The greater degree of sympathy for bicyclists among 18-34-year-olds may reflect this age group’s greater propensity to ride a bike. Fully one-in-six in this generation (17%) ride a bicycle at least once per week. That’s nearly three times as many as those who ride a bike this often among the 55-plus age group.

Similarly, as seen in the following graph, more than seven-in-ten of these oldest respondents say they never ride a bicycle, compared to fewer than half of those in younger age groups:

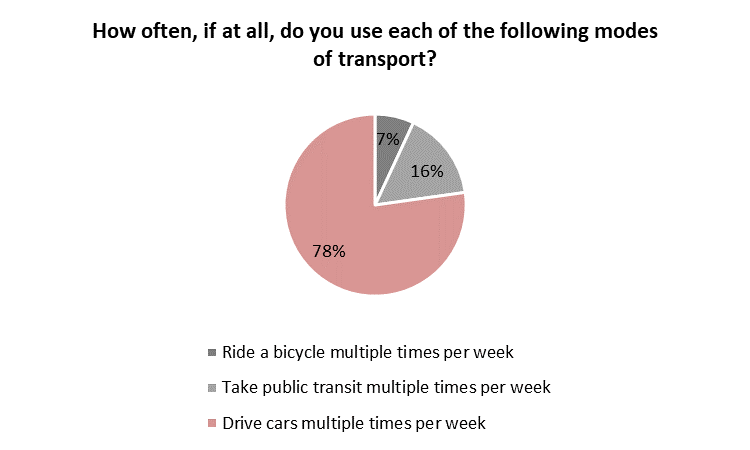

Bicycles are a much less common form of transportation in Canada than driving or taking public transit. Overall, 7 per cent of Canadians surveyed in this study ride a bicycle multiple times per week, compared to 16 per cent who take transit and 78 per cent who drive with the same frequency. These numbers are roughly comparable to Statistics Canada data for commuters’ modes of transportation.

Not coincidentally, those who ride a bicycle multiple times per week are considerably more likely to blame drivers for disputes between the two groups on the roadways. The much larger portion of the population that drives a vehicle multiple times per week, meanwhile, is more likely to blame cyclists. Frequent public transit users are divided on this question, as seen in the graph that follows.

While these divisions are significant, it’s worth noting that respondents were asked to assign blame to the side “more responsible” for conflict between drivers and cyclists. Asked to consider this issue in a different way, Canadians are inclined to find fault with both groups.

Two-thirds of Canadians (67%) agree with the statement, “Too many cyclists in my community don’t follow the rules of the road,” and a nearly identical number (64%) agree that “too many drivers in my community don’t pay enough attention to bikes on the road.” Majorities agree with each of these statements across all provinces and metro areas, as do majorities of frequent cyclists and drivers, suggesting that each group sees room for improvement within its own ranks.

How many separated bike lanes is too many?

Asked to weigh in on the number of separated bike lanes in their communities, Canadians are similarly reserved. After excluding those respondents who say there aren’t any separated bike lanes in their city or town, the percentage of Canadians who say their community has too few such lanes lags behind the percentage who view such lanes as a good thing, overall, as will be discussed in the final section of this report.

Indeed, in two metro areas – Calgary and Edmonton – respondents are more likely to say there are too many separated bike lanes than too few. Metro Vancouver residents are split, while east of Winnipeg, the call is for more lanes than fewer:

The strong sense that there are too few separated bike lanes in Winnipeg comes less than a year after a serious crash in which a bicyclist was pinned underneath an SUV, spending 62 days in a coma. The driver was later charged with dangerous driving causing bodily harm.

Winnipeg has been investing millions of dollars in cycling infrastructure in recent years. Cycling advocates pointed to the crash as a sign of more work to be done.

That said, those who ride their bikes multiple times per week are largely in agreement that there aren’t enough separated bike lanes where they live:

Most see separated bike lanes as a good thing overall

In recent years, the construction of separated bike lanes has become a key focal point of the “cars versus bikes” debate. Cycling advocates say the presence of a physical barrier between the car lanes and the bike lanes on a roadway makes it safer to ride a bicycle and, in turn, encourages more people to ride.

Opponents of separated bike lanes argue that they take up road space that could otherwise be used for parking or vehicular traffic, which increases congestion on the roads.

Presented with these two perspectives, a large majority of Canadians (65%) take the position that separated bike lanes are a good thing. Indeed, roughly as many respondents are unsure as say dedicated lanes for bicycles are a bad thing:

The belief that separated bike lanes are a good thing is the majority view in every metro area in this survey except those in Alberta, where it is still the most common view, though held by fewer than 50 per cent of respondents:

Similarly, more than seven-in-ten Canadians agree with the statement, “In general, bike lanes make a community a better place to live,” while fewer than half (48%) agree that, “Ultimately, roads are for cars, not bikes.”

The Angus Reid Institute (ARI) was founded in October 2014 by pollster and sociologist, Dr. Angus Reid. ARI is a national, not-for-profit, non-partisan public opinion research foundation established to advance education by commissioning, conducting and disseminating to the public accessible and impartial statistical data, research and policy analysis on economics, political science, philanthropy, public administration, domestic and international affairs and other socio-economic issues of importance to Canada and its world.

Click here for the full report including tables and methodology

Click here for the questionnaire used in this survey

MEDIA CONTACTS:

Shachi Kurl, Executive Director: 604.908.1693 shachi.kurl@angusreid.org @shachikurl

Dave Korzinski, Research Associate: 250.899.0821 dave.korzinski@angusreid.org

Ian Holliday, Research Associate: 604.442.3312 ian.holliday@angusreid.org